The division of the Church of the East and the story of Yohannan Sulaqa

Introduction

The Church of the East (Eta ed Mèdenha) has known many internal conflicts throughout history, but since 1552 it has had a development process, which is rather complex and has had quite major organisational consequences[1]. This development was largely influenced by the Roman Catholic Church.

Within the Church of the East (Eta ed Mèdenha), 1552 is known as the birth of the Chaldean Catholic Church, founded by Yohannan Sulaqa, a monk and head of the Raban Hormizd monastery near the village of Alqosh.

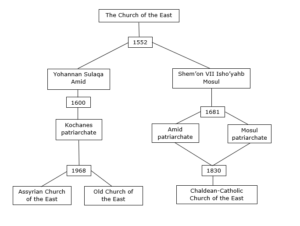

In this article we will however see that Yohannan Sulaqa and his successors are the founders of the Assyrian Church and the Old Church of the East and that only in the year 1830 there is talk of a Chaldean Catholic Church, where Chaldean always referred to the people and not as one dares to claim to the church concerned. The Chaldean Catholic Church also follows the original line of the patriarchs of the Church of the East (see figure 1).

Autonomous Church

The Church of the East had already become autonomous since the 5th century and was characterized by ‘Nestorian heresy’. Nestorius, a 5th-century patriarch of Constantinople, was deposed and banished because of his Christian views.

The label Nestorian was in fact a name that was wrongly given to the Christians of the Church of the East, because since the 5th century these Christians largely followed the Christian views of Theodore of Mopsuestia, better known as the duophysite doctrine. The visions of Nestorius were in line with this and therefore the Christians of the Church of the East were also called Nestorians. A “heretic” name that they did not have any difficulty with at the time and which in fact cannot really be called heretical.

This ‘Nestorian heresy’ was thus the result of theological conflicts in the 5th century, in which the Church of the East had distanced itself from the then patriarchates (Rome, Alexandria, Antioch, Constantinople and Jerusalem) and created autonomy. However, this changed from 1552 onwards.

Approach to the Roman Catholic Church

In 1539 Shem’on VII Isho’yahb succeeded his brother Shem’on VI as patriarch of the Church of the East.

During his reign, the Patriarch Shem’on VII Isho’yahb suffered a lot of headwinds from bishops, priests, monks, etc., because he made rather controversial decisions. Examples are the appointment of his twelve year old nephew Hnanisho as Mosul metropolitan and natar kursya (protector of the chair) in 1539, and the appointment of his fifteen year old brother Eliya (the future patriarch Eliya VII) as metropolitan in 1543.

Because of these provocative appointments and other matters, the Patriarch Shem’on VII Isho’yahb became so unpopular that his opponents began rebelling against his authority.

The rebellious bishops, priests, monks etc. met in Mosul in 1552 and elected a new patriarch, Yohannan Sulaqa.

However, there was no metropolitan who could bless Yohannan Sulaqa as a patriarch, as canon law prescribed. The proponents of Yohannan Sulaqa decided to legitimize his position by the blessing of the Pope of Rome Julius III.

Yohannan Sulaqa left in 1552 via Jerusalem to Rome. Sulaqa had documents with him, in which it was announced that the current patriarch Shem’on VII Isho’yahb had died in 1551 and that he was legitimately elected as the new patriarch.

As the Roman Catholic Church was unable to verify the accuracy of this information and Sulaqa profiled himself as a good Catholic, Pope Julius III announced on February 20, 1552, that Sulaqa would become the new ‘patriarch of Mosul’. On April 9, 1553, Sulaqa was blessed as a bishop and archbishop in St. Peter’s Basilica. On April 28, 1553, Sulaqa was finally recognized as a patriarch.

From this period onwards, the Church of the East was confronted with a permanent schism and a rivalry between the Catholic and non-Catholic camp. From then on there were two patriarchs within the Church of the East.

The fate of Yohannan Sulaqa

Yohannan Sulaqa returned to Mesopotamia at the end of 1553 and settled in Amid (Diyarbakir). He received documents from the Turkish authorities in which he was recognized as head of the Chaldean nation, following the example of all the patriarchs.

After only five months Yohannan Sulaqa blessed metropolitans for Gazarta, Hesna d’Kifa and for three new dioceses, Amid, Mardin and Seert.

The already existing patriarch Shem’on VII Isho’yahb saw this as a challenge and reacted by blessing metropolitans in 1554 for Nisibis (Nusaybin) and Gazarta. Shem’on VII Isho’yahb also made sure that the governor of Amadiya was on his side.

Yohannan Sulaqa left in 1554 for Amadiya where he was invited by the governor of Amadiya, but was unexpectedly captured for four months, tortured and finally murdered in January 1555.

The patriarchal line of Yohannan Sulaqa

After the death of Yohannan Sulaqa in 1555, the patriarch Shem’on VII Isho’yahb also died.

Shem’on VII Isho’yahb was succeeded by his nephew and ‘natar kursya’ Eliya VII. And Yohannan Sulaqa was succeeded by Abdisho IV Maron, the newly ordained metropolitan of Gazarta.

It was not safe for Abdisho IV Maron in Amid and so he stayed until his death in 1570 in the Mar Yaqob monastery near Seert.

Abdisho IV Maron was succeeded by Shem’on VIII Yahballaha who was a patriarch until his death in 1580.

The fourth patriarch in the line of Yohannan Sulaqa was Shem’on IX Denha, Salmas metropolitan who had been converted to Catholicism by Eliya Asmar, a friend of Sulaqa and Amid metropolitan. Shem’on IX Denha stayed in Salmas (Iran) during his reign.

Politics of Rome

By the end of the 16th century, the Church of Rome had learned the truth about the circumstances that had divided the Church of the East in 1552.

The Vatican therefore maintained contacts with both patriarchs with the aim of eventually creating a unified Catholic Church of the East.

However, this was a difficult process, and in the end it never succeeded.

The Kochanes patriarchs

The patriarchal line of Yohannan Sulaqa, also known as the unified patriarchs, took a major turn in 1600. After Shem’on IX Denha, Shem’on X became a patriarch in the line of Sulaqa.

Shem’on X moved his patriarchate to Kochanes in the remote Hakkari Mountains, making communication with the outside world almost impossible.

The decision to move the patriarchate to Kochanes had drastic consequences, in the sense that an association with the other patriarchal line had become an impossible task for the Vatican.

The Vatican’s hope to have a Catholic patriarch in the seat of a unified Church of the East was thus dented enormously.

Shem’on X created a new patriarchal line, known as the Kochanes patriarchs, which until today would never be united with the Roman Catholic Church.

The Kochanes patriarchs are thus the real successors of Yohannan Sulaqa, in the sense that they have continued the branched off line of the original Church of the East.

This branch remained “Nestorian”, as they never accepted the doctrine of the Roman Catholic Church.

In the second half of the 20th century, this Nestorian branch of the Church of the East, which remained in the second half of the 20th century, splits into two branches: on the one hand, the Assyrian Church of the East and, on the other, the Old Church of the East.

The Mosul and Amid Patriarchs

While the successors of Sulaqa in Kochanes were far removed from contact with the Roman Catholic Church, the Catholic influence in Amid (Diyarbakir) and on the Mosul patriarchy was fairly strong.

The Mosul patriarchs, successors of the original line of the Church of the East, remained for a long time after 1552 “Nestorian”, but would eventually succumb to the Roman Catholic doctrine.

But also this did not go so smoothly and led to the creation of a temporary third patriarchate, namely that of Amid (Diyarbakir).

The metropolitan of Amid, Joseph, was converted to Catholicism in 1672, partly by French missionaries. The then patriarch of Mosul, Eliya X Yohannan Marogin, had expressed his dissatisfaction with this and demanded his conversion back.

Joseph refused to convert back and was appointed in 1681 with the support of Rome as an independent patriarch of Amid and was accepted as such by the Turkish authorities after some conflicts.

Joseph had the patriarchal title Joseph I and had a total of three patriarchs and a patriarchal administrator as successors to the temporary patriarchate of Amid (Diyarbakir).

The patriarchate of Amid existed for a total of 146 years alongside that of Mosul and Kochanes. However, in 1827 the patriarchate of Amid was suspended by Rome, as all their hopes were placed on an ultimate attempt to unite the Mosul patriarchate with the Roman Catholic Church.

Association with the Roman Catholic Church

Where the attempted union with the Roman Catholic Church in 1552 failed, it looked as if a final association would be realized in the beginning of the 19th century.

Eliya XII Denha (1722-1778), patriarch of Mosul, was succeeded after his death by his nephew Eliya XIII Isho’yahb.

Eliya XIII Isho’yahb converted to Catholicism together with his cousin Yohannan III Hormizd, but after his appointment as patriarch he left the Roman Catholic doctrine again.

As a reaction to this Yohannan III Hormizd was appointed by Rome as patriarchal administrator of Mosul in 1780.

Yohannan III Hormizd was Mosul’s patriarchal administrator for a turbulent half century. In 1830 he was finally appointed patriarch of the Chaldeans and became the first patriarch of the Chaldean Catholic Church of the East.

A Catholic Church of the East was not established until 1830.

[1] Wilmshurst, D., The Martyred Church, A History of the Church of the East, East & West Publishing Ltd, Londen, 2011, 522 pages, (see chapter 8).