Historical book abused by Assyrian nationalist from Mechelen

Introduction

On February 27, 2024, an Assyrian nationalist from Mechelen published a message via social media in which he announced that he had written a letter. In the letter he refers to an attached document. In this document, according to him at least, the Vatican would speak out about the origin of the modern Assyro-Chaldeans and emphasize that they are the descendants of the ancient Assyrians. According to him, this is a clear position of the Vatican.

So much for the background information that prompted us to investigate this document. We carry out a fact check, so to speak.

Closer examination of the document in question reveals the following:

- The original text in Italian has been deliberately incorrectly translated into English.

- An important sentence in the text is deliberately not translated.

- The text is part of a Vatican statistics book and has been completely taken out of context.

Below is the analysis:

First of all, it is important to know that the writer of the original text was a priest who wanted to outline the ecclesiastical history of the Chaldean Church in broad strokes and had no intention of writing anything about the ethnicity of the Chaldeans, let alone to take a position on this issue on behalf of the Vatican. It is also important that the incorrectly and incompletely translated sentence is not a statement the writer is making.

The text in question has no doctrinal character, does not contain a historical statement about an ethnicity and is not a position of the Vatican.

Deliberately mistranslated

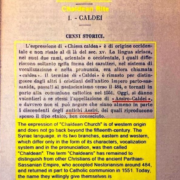

What is first noticeable is that the original Italian text (see image 1) has not been translated completely correctly into English.

The phrase “almeno in parte” means “at least partly.” The English translation should be: “at least partly”. However, it has been translated as “last in part”, which reflects a completely different meaning, namely: “the last in part”

This was a deliberate mistranslation, because the emphasis was on “last”, which would apply to the ‘last descendants’. However, in the Italian text there is no mention of the word “last”.

It seems like a small difference, since it concerns one word, but the difference between the incorrect and the correct translation is immense when we visualize the translator’s motive, namely trying to show that it concerns a people who are the last descendants of the ancient Assyrians and not at least partly as the text suggests.

Please note, this does not say anything about the reliability of this information, but it already shows that the translator deliberately misuses the text.

Original Italian text:

Oggi, si dànno volentieri a se stessi l’appellazione di « Assiro-Caldei », e davvero non si puo negare che siano almeno in parte i discendenti degli antichi Assiri, dei quali riproducono spesso il tipo etnico, ben conosciuto.

Incorrectly translated text:

Today, the name they willingly give themselves is “Assyrio-Chaldeans”, and it really cannot be denied that they are last in part the descendants of the Ancient Assyrians.

Correct English translation:

Today they like to call themselves “Assyro-Chaldeans.” “, and it really cannot be denied that they are at least partly the descendants of the ancient Assyrians, whose well-known ethnic type they often reproduce.

Deliberately incompletely translated

As we can read, in the English translation a period is placed after “the Ancient Assyrians”, while in the Italian text there is no period, but a comma followed by a not unimportant sentence. The phrase »dei quali riproducono spesso il tipo etnico, ben conosciuto» means “whose known ethnic type they often reproduce”.

To understand this sentence we need to focus on the verb “reproduce”. This verb can have the following meanings: “to imitate”, “to procreate” or “to multiply”.

In this context, the meaning “imitate” applies because it is followed by “whose known ethnic type they often…”

Twee zaken dienen hier opgemerkt te worden:

1) A text should never be translated incompletely, because then the context will not be reflected correctly. One can say that one has only translated a relevant part of the text, but this is a sentence that has not been fully translated, which makes the translation unreliable in any case.

2) The question should be asked why the full sentence is not translated. The writer of the Italian text wants to make it clear that those who then wished to call themselves Assyro-Chaldeans often imitated the well-known ethnic type ‘Assyrians’, in the sense that it no longer existed, but had a certain historical fame and they wanted to bring it back to life. As you will notice, this omitted sentence gives a completely different twist to the story.

Taken out of context

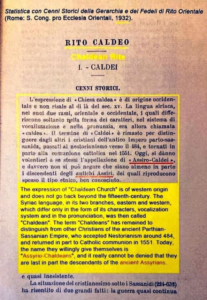

We are talking here about a statistical book drawn up by the Congregation for the Eastern Churches (see image 2). This is a department (kind of ministry) of the Vatican that was founded in 1917 and has since been replaced by the Dicastery for the Eastern Churches.

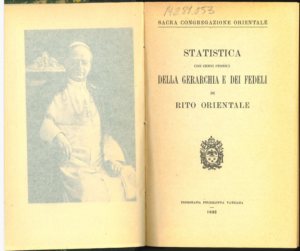

This book was compiled by several people with the intention of collecting information about the various Eastern Churches that were united with the Roman Catholic Church at the time (see image 3). The Chaldean Church was also discussed.

However, this book does not intend to provide information about the different ethnicities of these church communities, that is simply not the case.

Moreover, the writer very clearly states that it is not the Vatican that gives the name “Assyro-Chaldeans”, but it is “those who want to call themselves that today” and “those who want to reproduce the known ethnic type”.

As readers will further note, there is no further mention of Assyro-Chaldeans in this book, except in the relevant sentence, which has been deliberately mistranslated and incompletely translated by the translator. (Doc. 1) It also discusses statistics of the Eastern Churches with historical notes in the context of their church history.

In short, the sentence in question should not and cannot be read in its entirety as a position of the Vatican, nor as a statement by the writer.

Assyro-Chaldeans

Another important fact that should be taken into account here is the period in which this book was published, namely in 1932. The idea of an ethno-cultural link with the ancient Assyrian empire has its origins in the 19th century, more specifically after the British archaeological excavations in the Northern Iraq region (more about this in the article Assyrian nationalism). From the 20th century onwards, this idea was used to push for an autonomous Assyrian Christian region in Iraq. That is why the writer of this text also clearly states, “Nowadays they like to call themselves Assyro-Chaldeans.”

We could argue about who the writer means by “they” . For the sake of clarification, we can say that “they” cannot possibly refer to the Chaldeans of the Chaldean Catholic Church, because if that were the case, they would simply have called the name of their Church that, which was not the case.

“They” rather refers to the Assyrian nationalists who at the time worked for an autonomous Assyrian Christian region in Iraq. It concerned the Christians of the Church of the East who had not become Catholic in the previous centuries.

To reinforce this goal, the nationalists sought unity with the Catholic Chaldeans. For this purpose, the term “Assyro-Chaldeans” had been unilaterally created under British and French political influence. This term would serve to name the Catholic Chaldeans and the so-called non-Catholic ‘Assyrian’ Christians (at that time there was not even a mention of the Assyrian Church).

What is often forgotten is that the non-Catholic Christians, who since then began calling themselves Assyrians, also identified themselves as Chaldeans until the 20th century.

Today, the term Assyro-Chaldeans is not intended to create unity, but rather to state clearly that Assyro stands for the Assyrian ethnicity and Chaldeans for the Chaldean Church. One can say here that they have made it a contradictio in terminis (Latin for “contradiction in terms”).

To be clear, it was also the translator’s intention to link the term Assyro-Chaldeans with the ancient Assyrians by means of this deliberately incorrectly and incompletely translated propaganda text.

Origin of the name Chaldean Church

The text also gives us valuable information about how the name Chaldean Church came into being. It is clearly stated that this was based on their spoken language which was called Chaldean. On this basis, the term Chaldeans has also been used to distinguish these Eastern Christians. Rather, one historical piece of evidence that Assyrian nationalists believe would work in their favor is confirmation that the term Chaldean was not reinvented by Rome.

Assyrian nationalism

Assyrian nationalism, which has its roots between the First and Second World Wars, has clearly reached its zenith in the 21st century. In the absence of reliable historical sources that can possibly be used as arguments, historical sources are abused in this way in the context of propaganda.